It is a quite common situation: the musician learns to read sheet music but, for various reasons, ends up being dependent on this graphic representation. We often forget that the score is not music, just as a printed text is not the message in its essence, but only paper and ink that are intended to help convey concepts with some precision and, at best, intentions. Feelings or emotions are left out, naturally! These human values only arise… within the human being. Text, images, and even words and chords can act, at best, as catalysts of emotions, feelings, desires, imaginations, and other impalpable attributes of the human mind and heart.

So you might ask, what is the musical score for then?

Of course, it has its use. But to a certain extent…

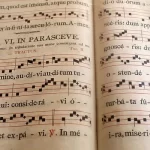

Notes and staves are faithful records, universally accepted, of musical creation, be it newborn or already counting centuries of age. Thanks to the score (because the recording systems only appeared in the first half of the twentieth century and the oral tradition has many limitations of temporal and geographical order), thousands of works of countless styles, true treasures for our ears and hearts, have reached us who live immersed in a world of endless turmoil. Most of these compositions appeared from the 14th century on, although some rudiments of musical record (e.g., carved wood, parchment, or engraved pottery) had already occurred at least 4,000 years ago.

Registration and Memory

After this introduction, it would be great naivety – and perverse ingratitude – to despise the immense work of our ancestors to develop some form of musical writing. This commitment has served – and will continue to serve – several purposes.

Right from the start, it is necessary to recognize the score as a tool for recording ideas and passing them on to other people – from the present or future. It is also indispensable to the teacher or musical pedagogue in his task of creating varied studies for instrumentalists and music lovers and thus helping these people in their improvement, both as a human being and as a professional musician.

Musical Analysis

We also have the valuable and irreplaceable support of the score when, in our studies and analysis of music – or even in auditions for pure pleasure – we accompany “with a magnifying glass” the written music, following the melodic lines and harmonic schemes ingenuously elaborated by its creator. How much ingenuity and beauty can we thus confer and contemplate, listening, for example, to a cantata by Bach and having his score in hand? Or discover how the disconcerting timbres emerge, elaborated from innovative combinations between orchestra instruments, in a symphony by Brahms or the piece Jupiter, from the symphonic poem The Planets, by Gustav Holst. Only those who have done this can appreciate how fantastic and enriching this experience is.

Ink and Paper

However, as already mentioned, registration is a means of transmitting ideas in their original state. But it is not music, the sound-art phenomenon that attracts and seduces millions in all cultures of the planet (Naturally, a gifted aural skilled musician, looking at a score, can “listen” internally to the composition in a quite accurate way compared to a “real” hearing of that same song. But remember… approximately. To result in music, the score needs to be performed by one or more musicians, using the voice, body, or any kind of musical instrument. And it is precisely at this moment that the great magic is completed. A multitude of printed figures becomes a sound stream that penetrates us through the ears (but also through the skin!) and addresses the soul, giving birth (or reinforcing) a myriad of sensations, emotions, memories, images, dreams, and potential inspirations for other areas of life. In short, generating joy, satisfaction, pleasure, melancholy, courage, health, etc.

The Path of the Apprentice

To begin our evaluation, it is important to consider the generic development of learning a new song by an instrumentalist. In such a situation, we can divide the process into two distinct moments, an initial and a conclusion. That is, the first contact of the musician with an unknown score and the scope of his goal – the “finished” execution of the piece.

Now, consider what happens between these two points. Initially, the musician needs to make a reading of the symbols printed on paper (or screen): staff, key signature, time signature, notes, accidents, ties, slurs, dynamics, repetitions, etc. Depending on his previous experience and the style of musical writing considered, this phase may be slower or faster. It is also natural that, here, the musician comes across new material – new rhythmic and melodic sequences, innovations in voice conduction and the structure of chords, bigger jumps for the hand, and many others. And here the score is indispensable. But as time passes in contact with the piece, a more internal instance than the vision – the ear and its connection with memory – begins to assume the learning. In this process, the score gradually becomes unnecessary, more and more expendable. More than that, after a certain point, for most musicians, the act of observing notes, fingerings and various other signs present in the score can hinder the improvement of interpretation. This is quite understandable, because as the music becomes fixed in the musician’s memory, the sense of vision becomes unnecessary and, if used, can even be a hindrance to reaching perfection. This is easily observed when we see an expert instrumentalist playing a piece, so surrendered to the experience that, even with open eyes, he seems totally absent from the environment in which he finds himself. Just as it is equally common to watch musicians playing with their eyes closed, in addition to the frequent cases of accordionists – and other musicians – blind.

Memory instead of Sheet Music

In the world of accordionists, it is very rare to see a musician using sheet music on a stage. In the universe of popular music, this is even easy to understand, since this style gives space – and even stimulates – for a considerable margin of freedom to the musician, who, for this reason, never repeats (in all aspects and I should stress: NEVER) the performance of any piece. Therefore, there would be no reason for the use of sheet music. However, even among accordionists who dedicate themselves to classical music – traditionally written note-to-note on paper, it is common to watch fully performed by-heart interpretations! And so the musical result is usually impeccable.

Returning to popular music, Brazilians has a typical example of an extraordinary musician who never made use of sheet music – because, it is said, he did not know the formalities of musical writing: Dominguinhos. For many the greatest accordionist ever heard in Brazil, Dominguinhos was admired even by other great instrumentalists who worked with him. If it weren’t for his fear of flying, Dominguinhos would be considered worldwide as one of the greatest accordionists of all time!

In the End, Everything Leads to Music!

To conclude this article, I hope it helped deepen the understanding of the role of the score in the music experience. It is an excellent tool to register and develop musical ideas – melodies, rhythmic patterns, harmonic schemes, etc – and to spread the composition among other musicians. It also helps legions of educators and musicians organize the teaching and learning of their instruments. Composers rely in scores a vital element for analysis of works of the great masters. It therefore desserves its space to ensure the perpetuation of musical art. But its biggest role, it’s worth remembering, is to help spread the art of music and make it reach its final destination, with the highest possible quality: our ears (and not our eyes).

Feel free to express your thoughts and share your experiences about the relevance of score in your life as a musician.